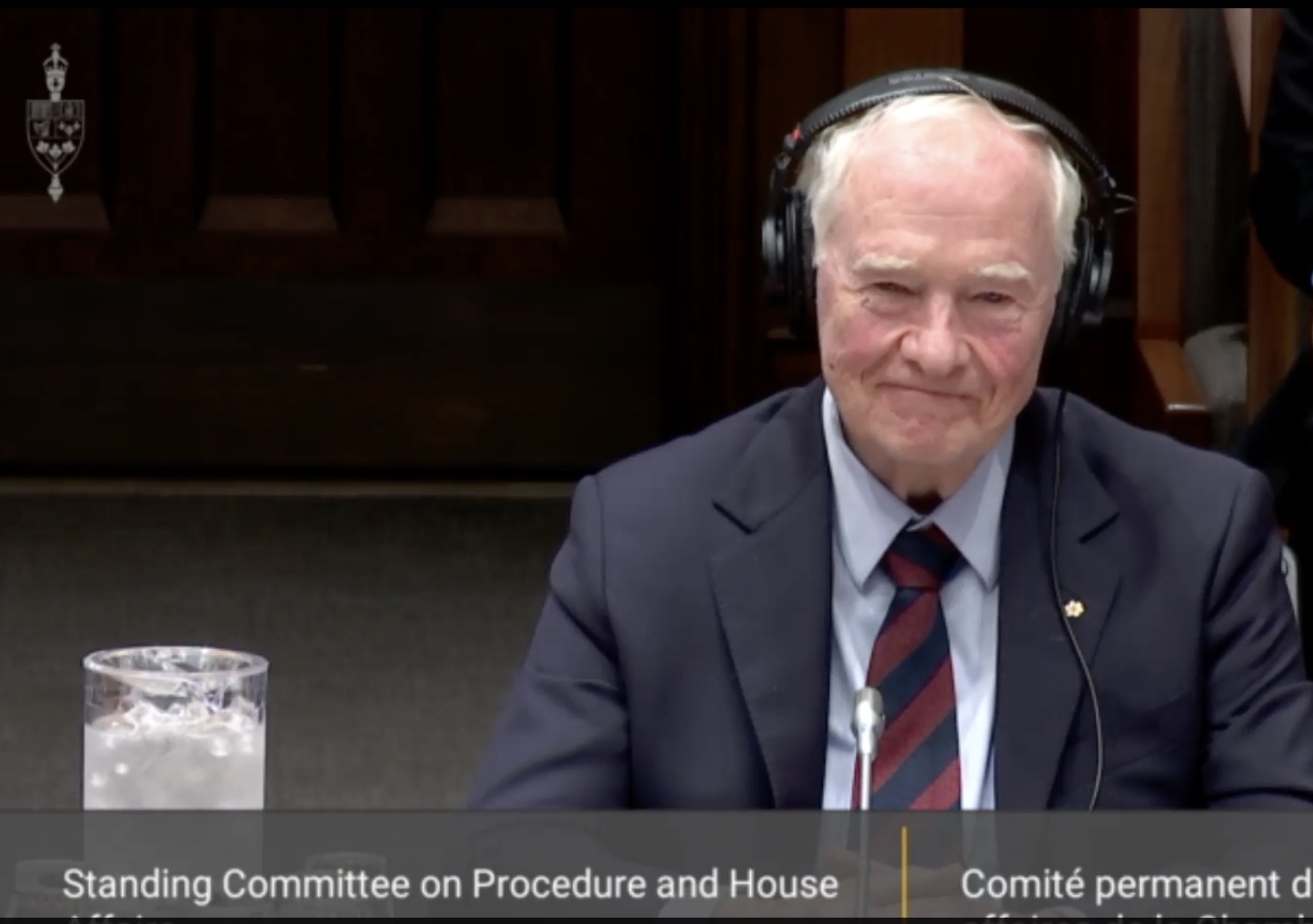

The former Governor General, David Johnston, tells us foreign governments are trying to influence voters and candidates and it is a real and growing threat.

In his report published one month ago he identified shortcomings in the way intelligence is communicated and processed from the security agencies to the Government. But he rejected calls for a public inquiry on the grounds this would put at risk information that has to stay secret. He preferred public hearings. He believed State secrets would then be protected and these would only be made available to top politicians and others with the highest security clearance.

Rejected

MPs heard what he had to say and then politely rejected his advice. They voted for a public inquiry which, the Government says, is now back on the table. But since then all has gone quiet.

If we are to get to the truth, we need a public inquiry with subpoena powers and witnesses giving evidence under oath. The parties now need to agree the inquiry’s terms of reference and decide on a chair and a timetable which is not open-ended.

That’s difficult but not impossible.

The Globe and Mail’s Andrew Coyne summed it up this way:

We need an inquiry to get at the things that cannot otherwise be got at: the internal decisions and deliberations of government. We do not need such inquiries at most times. We need them when government has made a mess of things, and won’t come clean about how it happened. We need an inquiry most when a government is most reluctant to hold one.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Update on 31 July 2023: Toronto Star Editorial: Slow Steps to an Inquiry

From the Globe and Mail 14 June 2023

Four moments of truth for a public inquiry into election interference

Some cracks in the Liberals’ stonewalling over China’s election meddling are finally opening up, creating at least the hope of some light being brought to bear on Beijing’s interference in two successive federal campaigns.

The resignation of former governor-general David Johnston as special rapporteur fatally undermined the not-an-inquiry approach that the Liberals had hoped to skate by with. Now, the government says it is open to a public inquiry, and could the opposition leaders please figure out how that could happen?

Perhaps that proposal, floated by Intergovernmental Affairs Minister Dominic LeBlanc on Saturday, is an olive branch extended in good faith. Perhaps, and much more likely, Mr. LeBlanc and the Liberals hope that the opposition parties will rip that branch to shreds, and be unable to agree upon the particulars of a public inquiry. That is a real danger, as is the flip side. If the opposition parties do hash out a framework, the government discards that proposal at its peril.

Each party leader faces his own moment of truth.

The stakes are the most obvious, and the smallest, for Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet. He needs to demonstrate that the Bloc can play a constructive role in the House. So far, he appears willing to do so, telling reporters this week that his goal is to reach a consensus on the details of a public inquiry. He sensibly noted that the person, or persons, heading an inquiry should determine what information remains classified.

The calculus is more complicated for NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh, who for weeks has been a) harshly criticizing the government over its refusal to call a public inquiry and b) propping up that same government through a 14-month-old formal parliamentary alliance. Notably, Mr. Singh did not withdraw from that agreement when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau invented the position of special rapporteur in early March rather than call a public inquiry.

The NDP Leader will not be able to avoid that choice this time around. If the Liberals refuse to call an inquiry – not a consultation, not a hearing, not a “public process,” as Mr. LeBlanc hinted – then Mr. Singh will need to axe his alliance. Otherwise, he will bear joint responsibility with the Liberals for the erosion of trust in the electoral system and for the continuing failure to remedy the institutional weaknesses that have enabled Beijing’s foreign interference.

Mr. Singh’s challenge is to be ready to break with the Liberals, but that of Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre is the opposite: he needs to show Canadians that he can do more than simply lambaste the Liberals. To be sure, this is a government in need of lambasting on the question of foreign interference. The Conservatives have justifiably (if at times caustically) decried the Liberals’ resistance to calling a public inquiry.

But Mr. Poilievre needs to go further, and prove that his interest lies in a timely public inquiry, not in a protracted pillorying of the government. The Conservative Leader is giving early indications of such proof, saying that he has “no problem” with including China and Iran in the scope of an inquiry. His initial comments to reporters on the qualifications for an inquiry commissioner also seem reasonable: someone with no ties to the Trudeau Foundation, or problematic foreign regimes, and with a history of non-partisanship.

All three opposition leaders have rightly called for a tight time frame for an inquiry to ensure that any needed reforms are in place before the next election.

The question is, will Mr. Trudeau listen? It was telling that Mr. LeBlanc dissembled when asked directly on Saturday whether the government would agree to terms proposed by the opposition parties. “We have to see who they’re going to suggest, we have to see the terms of reference,” he said.

Meanwhile, Mr. LeBlanc several times voiced the Liberals’ desire for a “public process,” while notably failing to unequivocally commit to a public inquiry with subpoena powers. The Liberals cannot both insist that the onus is on the opposition to come up with a process and then simultaneously dismiss that effort.

That is the moment of truth for Mr. Trudeau. Will the Prime Minister, finally, realize that the integrity of the electoral system is of vital concern to all parties, not to mention all Canadians? And will he, at last, show that he understands that the country deserves clear answers to what the Liberals knew about foreign interference, when they knew it and most important, what they did about it?___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Postscript on the UK's Iraq Inquiry: Twenty years ago, at Westminster, I voted against the UK going to war with Iraq. The security and intelligence services told us Iraq had Weapons of Mass Destruction. But I didn’t see any credible evidence of their existence. The then PM, Tony Blair, desperately wanted a war with Iraq and the intelligence was deliberately embellished to help make the case. Many of the key players who voted for the war now accept it was a huge mistake and express deep regret.

The Butler Review on Weapons of Mass Destruction which reported in July 2004 did not meet in public. It took six months to conclude that Iraq did not have any WMDs. Despite this, the Government dragged its feet, refusing to set up a full public inquiry to find out what went wrong and why.

In 2005 the UK Parliament’s Public Administration Select Committee recommended that when the Government was unwilling to undertake an inquiry into an important matter itself, then Parliament should be able to do so. There was statutory authority in the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921. In 2008 the Committee revisited the issue and proposed a mechanism which would kick in when the Government refused to act – a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry. The following year the Government, now with a new Prime Minister (Gordon Brown) at the helm, set up the Iraq Inquiry under Sir John Chilcott which, scandalously, did not report until 2016 – 13 years after the war ended.

The Inquiry concluded:

The judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction – WMD – were presented with a certainty that was not justified.

Witnesses: How the Inquiry took evidence. The Inquiry Report explains:

"The majority of witnesses gave evidence in a public session. The Inquiry wanted hearings to be as accessible to the public as possible, so in addition to having ticketed (free) public access, sessions were also available for broadcast on television and over the internet. The recordings can still be viewed on the Inquiry’s website. The first public hearing was held on 24 November 2009 and the last on 2 February 2011.

The Inquiry heard from 35 witnesses in private. The circumstances in which the Inquiry agreed to hold private hearings are laid out in the Witness Protocol. In some cases, evidence was heard in private because of a risk of damage to national security or other vital national interests. In others, it was due to the personal circumstances of the witnesses, or because of the organisations for which they worked. The names of some witnesses therefore do not appear, and are replaced by ciphers. Transcripts of these sessions, reviewed and certified by the witnesses as truthful, fair and accurate, can also be found on the Inquiry’s website. In many cases some material has been redacted by the Government in order to prevent potential harm to national security or international relations."